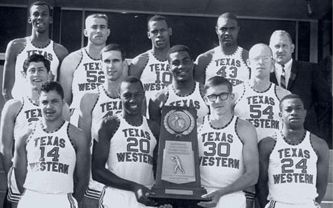

The Miners’ all-black starting five beat all-white Kentucky to win the NCAA men’s basketball title.

By Bruce Lowitt

To this day, coach Don Haskins and his Texas Western players will tell you that starting a revolution was the last thing on their minds.

“We were just kids playing basketball having fun. … It was not that big a deal to us,” center David Lattin said. “We were just out there trying to win.”

That they did. On March 19, 1966, the Miners, with five black starters, won the NCAA men’s basketball championship, defeating Kentucky 72-65.

No. 1 Kentucky.

All-white Kentucky.

“What a piece of history,” said Arkansas coach Nolan Richardson, who played on Haskins’ first team. “If basketball ever took a turn, that was it.”

Adolph Rupp, the Kentucky coach, was considered by many to be a racist. He had no African-American players, nor would he recruit any. New York Daily News columnist Mike Lupica wrote last year that Rupp, scanning high school boxscores, would call a newspaper when a high-scoring player’s name became familiar.

Lupica quoted Rupp: “I’m lookin’ at Boys High here. … This Connie Hawkins — 11 baskets, five free throws, 27 points — would he be white or colored?” Told that Hawkins, of Boys High in Brooklyn, was not white, Rupp replied: “Can’t you people put some kind of asterisk next to these names?” and hung up.

It was a time of racial unrest in the United States. There were black players on college teams in most areas of the country, but many coaches still believed their teams needed one or two white players on the court at all times to maintain discipline. Starting five black players simply wasn’t done — certainly not on the grand stage of college basketball’s championships.

“The teams that we were playing — like Arizona, Arizona State, New Mexico, New Mexico State — we were playing against black players all the time,” Haskins said. “It really wasn’t that big a deal. … I never thought a thing about it.

“But after we won the title with five black guys, everybody made a big deal out of it. My thought was, “You play your best five guys.’ ” And Haskins’ best seven were Lattin, Bobby Joe Hill, Willie Cager, Harry Flournoy, Nevil Shed, Willie Worsley and Orsten Artis — all African-Americans.

“A couple of white players came in and got the job done also,” Cager said. “Don Haskins played the best, the best people for the job. That’s all it was.”

This Kentucky team was Rupp’s favorite. “Rupp’s Runts” they were called, with no starter taller than 6-5. The Wildcats were all good ball-handlers and shooters. But they were slow compared with the Miners.

To utilize his team’s quickness, Haskins started a three-guard offense. He put the 5-6 Worsley on 6-3 Larry Conley. Rupp put in place an offense calling for Conley to shoot over Worsley. He did, but neither he nor his teammates could put their jump shots through the hoop very often.

The teams played even, if sloppily, through the first 10 minutes. When Shed sank a free throw, Texas Western went ahead 10-9. It never relinquished the lead. On Kentucky’s next two possessions, Hill stripped the ball from Tommy Kron and Louie Dampier, converting each steal into a layup. The Miners’ lead widened to 14-9.

Four minutes into the second half, Kentucky cut the lead to one. Then Hill and Artis combined for a six-point run. As time ran down, Texas Western started stalling to eat up the clock. Kentucky was forced to foul and Texas Western made the free throws, 28 of 34 in all. Hill finished with 20 points, Lattin 16 and Artis 15 to overshadow the 29 apiece by Dampier and Pat Riley.

The victory, Hill said, “was the thing that opened doors in the ACC, the SEC. … Everybody started recruiting blacks after that.”

Said Lattin: “It certainly made it possible for a lot of black kids to go to majority white colleges to get a better education. It was a significant point that turned racial issues around and made it possible for guys to get scholarships — and not just basketball. Football and baseball as well.”

Haskins coached at the school through last season before retiring in August. The Lubbock-based school is known now as the University of Texas El Paso. He never reached the Final Four again. That game is, to a degree, what defines him.

Two years ago, when he was voted into the Basketball Hall of Fame, author Frank Fitzpatrick interviewed him for And the Walls Came Tumbling Down, the story of the 1966 Texas Western team and championship game. “I’ll be honest with you,” Haskins said. “I’m sick of talking about the damn thing. Sometimes I wish we finished second.”

For more information about this event, click here!